Cover Story 1 / The State of the Nation: The Invisible Cost of SST

MORE often than not, consumers do not think about the sales or service tax they indirectly incur when purchasing goods from retail stores.

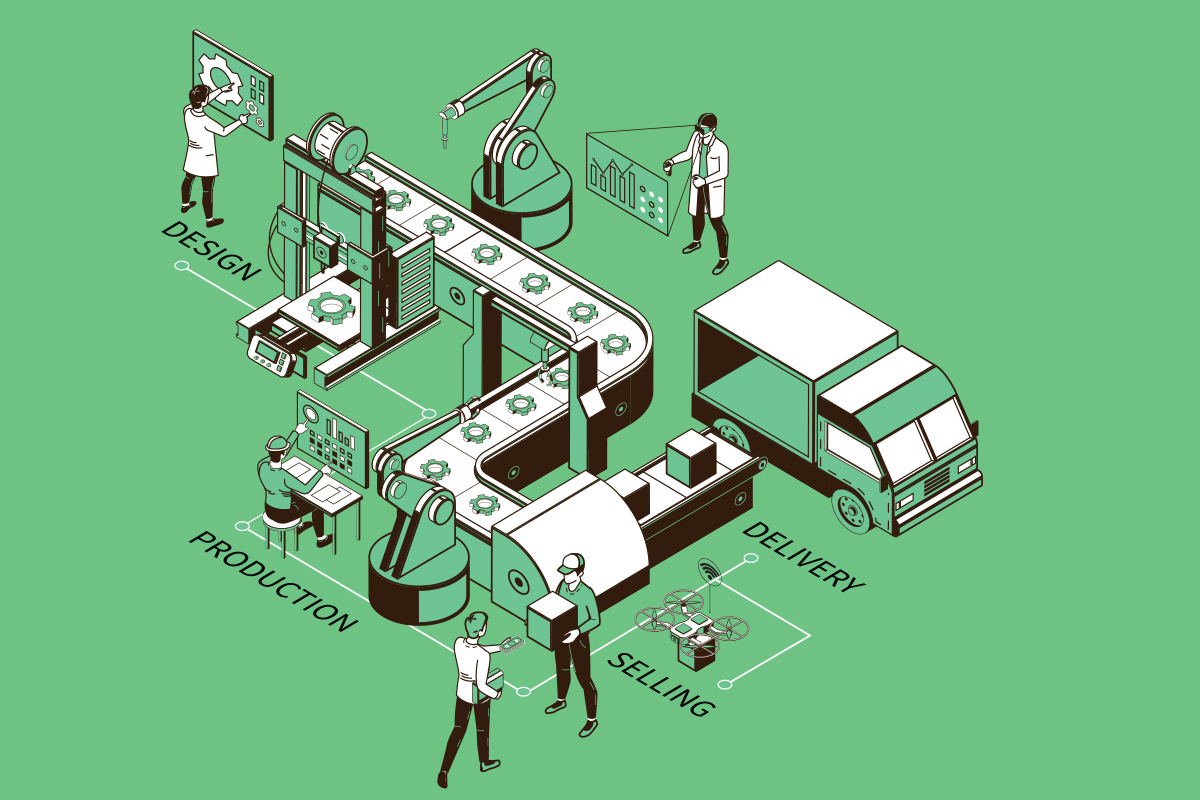

As the portion of the sales or service tax paid earlier on in the supply chain is not reflected in the receipt of the consumer’s purchase, it is invisible to the consumer — unless it is a service that the consumer directly incurs, such as having a meal at a restaurant, which attracts a 6% service tax.

The sales or service tax is a single-stage tax. The sales tax is collected at the manufacturer level at a general rate of 10% while the service tax — the proposed rate of which is 8% commencing in 2024 — is paid by the consumer (be it business or individual).

Being a final tax in nature, meaning that businesses do not get to claim a credit for incurring it, it creates a tax-on-tax effect along the supply chain. The effect is especially apparent in the service tax.

One example of this would be the property developer that incurs various services in order to bring a project to completion. At the very least, it would have to pay service tax on the accounting, IT and architectural services it uses. Unable to claim any input tax, the developer is likely to embed the service tax paid into its pricing for the said project. This essentially means the end-consumer is likely paying for the service tax incurred by the business — meaning higher prices — without realising it.

“Previously, a study was done on a chair manufacturer in Segambut. Chairs attract a sales tax of 10%. It was a fairly simple supply chain where the manufacturer sells its products to the marketing company, which then sells to the distributor and then to the retailer. The effective tax rate was 17.5% — that’s the cascading effect,” explains PwC indirect tax director Raja Kumaran.

“Even when dealing with non-taxable goods, businesses could have paid service tax on accounting, auditing or some other form of service, which will be a cost to the business. It can be quite significant because every business deals with another taxable person,” he points out.

Tax experts call the cascading or compounding effect one of the biggest weaknesses of the current sales and service tax (SST) regime, while the lack of transparency is seen as another downside to the indirect tax regime adopted by Malaysia.

TraTax Sdn Bhd executive director Thenesh Kannaa notes that there are a number of grey areas when it comes to the service tax, which is prescribed based on a list of taxable services.

“For example, warehouse management is listed as a taxable service, but there is an overriding provision that exempts management services related to logistics. There are no published guidelines to clarify when warehouse management is in fact taxable,” he observes.

“This leads to unsynchronised compliance until enforcement activity is conducted by the Royal Malaysian Customs Department. This matter should be improved.”

He adds that unclear policy goals are evident with the SST regime. He cites the example of a consumer who engages a technician to repair his air-conditioning unit and is not subject to service tax on the repair cost. However, if the consumer enters into an arrangement for proactive maintenance periodically, the maintenance charges are subject to service tax.

“The policy rationale is unclear. There are many aspects like this which should be studied and harmonised to influence consumer and industry behaviour in the right direction,” says Thenesh.

While the compounding effect is less of an issue for the sales tax as there are facilities available for manufacturers to apply for a tax exemption, it is not without problems either.

“There are exemptions available to manufacturers so they do not have to charge each other sales tax, but the manufacturers have to apply and ensure they meet the required conditions, which can be tedious,” says KPMG Malaysia indirect tax head Ng Sue Lynn.

Raja says many sub-manufacturers do not make use of the facilities available. Perhaps they are not aware of the facilities or how to apply for them, he muses. “It is also a hassle for smaller businesses with the monthly submissions, where they have to keep track of the raw materials, of what is tax exempt and not. So, they end up not applying for exemptions and they charge manufacturers the sales tax.”

8% service tax

During the Budget 2024 announcement, the government proposed to raise the service tax to 8% from 6% currently, except on food and beverages and telecommunications services. It said it expected a RM3 billion increase in revenue from the higher tax rate, but some experts believe the figure could be higher.

With the proposal to raise the service tax to 8% and widen the scope to include brokerage, underwriting, logistics and karaoke services, Ng thinks the actual impact may be more than the increase of two percentage points, from 6% to 8%. “The actual impact could be more than the two percentage point increase, but it would also depend on the complexity of the supply chain.”

Currently, only business-to-business transactions between certain professional services are exempted from service tax.

Thenesh opines that with the proposed increase in the service tax rate and wider scope of taxable services, it is crucial for the government to embark on initiatives to harmonise the sales tax regime and service tax regime to allow sales-tax-registered manufacturers to either claim input tax credit or allow tax exemptions on services procured by businesses.

No GST on the cards, what’s the solution?

At this juncture, the goods and services tax (GST) does not seem likely to be implemented for many reasons. Apart from being a highly politicised topic, tax experts also believe GST and the subsidy rationalisation efforts the government is embarking on cannot be implemented at the same time as it will result in higher inflation.

“It must be noted that the GST model introduced in 2015 was not a full-blown model as it had too many exemptions. It is recommended that a proper study be conducted for the introduction of a full-blown GST model in line with international standards. Until the economy, people and industry are ready for that, it is suggested to improve the present SST model,” says Thenesh.

Ng says the tax base can be widened and the government could relook the SST rate, but relief such as input tax credit should be given to businesses so as not to cause a spike in prices along the supply chain.

Raja opines that if the scope for SST were to be increased, it should be on services that do not have a direct impact on consumers. Nevertheless, he adds that it is not fool-proof because the cost will eventually be passed on to consumers indirectly.

More importantly, Raja emphasises that the government should work on plugging SST leakages, which are very high in Malaysia. Some estimates put the leakages for beer and cigarettes alone at some RM7 billion.

There is also a proposal to have a harmonised sales and service tax as proposed by the Malaysian Institute of Economic Research (see “HSST the next best option to GST, says MIER” on Page 10).

“The main challenge with the HSST is whether the government will lose revenue and how it can recover the potential amount of sales tax and service tax. If the rates for the sales tax and service tax are standardised, for example at 8%, except for high-value goods, the government would be able to recover some tax revenue. It is also easier in terms of documentation for businesses,” says Tricor Malaysia non-executive chairman Veerinderjeet Singh.

While many believe the HSST could work as an alternative for now given the difficulties of implementing GST, Raja does not agree.

“As for the HSST system, I don’t agree that it will work. We cannot have bubbles on bubbles of exemption. How do we determine who comes into each bubble and how do we manage when a person can be a member of multiple bubbles?” he points out.

One of the main reasons GST was introduced back in 2015 was to have better compliance through self-policing and indirectly bring the underground economy to light. But with the introduction of e-invoicing in Malaysia next year, which also aims to enhance compliance and bring to the surface the untaxed economy, some say it could put Malaysia in new territory.

“Most countries have implemented GST/VAT first and then further improved with e-invoicing. Given that Malaysia is set to introduce e-invoicing from next year, it remains a question as to whether GST would have any further contribution in reducing the size of the black or untaxed economy amid the robustness of e-invoicing,” says Thenesh.

In other words, if e-invoicing coupled with the expansion of the SST base and the increase in tax rates could amount to almost a similar effect under GST, will there still be a valid reason to reintroduce GST?

Tax experts still believe that Malaysia must head towards GST in the future. Nevertheless, they caution that if the tax were to be brought back, awareness must be created among the people and it has to be explained effectively. Furthermore, the rate cannot be too low (some had previously suggested to start at 4%) because it would result in a loss of tax revenue for the government, collecting an even smaller amount than the existing SST model.

“GST is still the most efficient mechanism but the challenge is to make sure the tax administration side of things is strong. It has proved to be efficient across many countries in the world. But since the political appetite for GST is weak, HSST could be the next best option for now,” says Veerinderjeet.

Regardless of which camp one is in, the main thing that should be agreed upon is that at the end of the day, taxes should not be solely driven by the need for revenue, but must also be fair, efficient and not result in burdensome compliance costs for businesses.

Source Credit: https://theedgemalaysia.com/node/688973